We know that men are more likely to rise to leadership positions than women. According to a CIPD review of FTSE 100 Companies in 2016 there were fewer female CEOs (6 in total) than CEOs named David (8) or Steve/Stephen (7). We also know that social networks are critical to professional advancement. This made me wonder: is there a difference between the networks of successful male and female leaders? And recent research suggests that there is.

Brian Uzzi, Professor of Leadership and Organizational Change at Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management, tried to connect social networks at business school to job placement success. He and his team analysed 4.5 million anonymized email correspondences among a subset of all 728 MBA graduates (74.5% men, 25.5% women) in the classes of 2006 and 2007 at a top U.S. business school. Job placement success was measured by the level of authority and pay each graduate achieved after school.

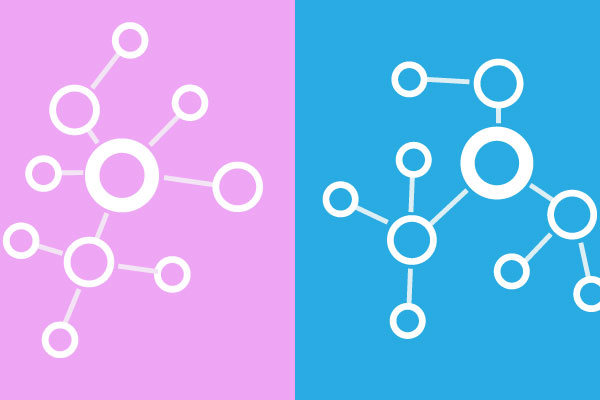

They confirmed that the social networks of men and women affected post-graduation job placement. Men and women benefit not so much from size of their network but from being central to their network, i.e. connected to other people who have a lot of contacts across different groups. Being central gave them the advantage of quick access to varied job market information, such as who’s hiring, what salaries are offered at different firms and how to improve their applications.

Women, however, also benefitted from an inner circle of close female contacts who could share private information about things like an organisation’s attitudes toward female leaders, which helps strengthen women’s job search, interviewing, and negotiation strategies.

Men Need Centrality

Men who had the most centrality (top quartile) in the MBA student network tended to perform best in the job market, securing jobs with more authority and pay (1.5 times greater) than their peers with the least centrality (bottom quartile). High centrality drove their placement even after controlling for individual characteristics, such as undergraduate coursework scores, test scores, sociability, country of origin, and work experience.

Centrality is positively correlated with accessing job market information, because even though much of the information about employers is publicly available online, it can be much faster to get the information you need from different MBA students who have contacts across various groups of students who are familiar with employers you’re interested in.

Women Need Dual Networks

Successful women have high centrality like successful men, but they differ in that they also maintain a close inner circle of female contacts. Although they could not review the content of email messages, Uzzi and his colleagues conjectured that this close inner circle of women is likely to provide critical private information on job opportunities and challenges. This private information might be about whether a firm has equal advancement opportunities for men and women, or whether an interviewer might ask about plans to start a family and the best way to respond.

Women who were in the top quartile of centrality and had a female-dominated inner circle of 1-3 women landed leadership positions that were 2.5 times higher in authority and pay than those of their female peers lacking this combination. While women who had networks that most resembled those of successful men (centrality but no female inner circle) found leadership positions that were among the lowest in authority and pay.

Women’s success also depended on a certain kind of inner circle. The best inner circles for women were those in which the women were closely connected to each other but had minimal contacts in common. The example they give is Jane, a second-year MBA student whose inner circle includes classmates Mary, Cindy, and Reshma. If these three have networks with few overlapping contacts then Jane will benefit not only from her three classmates but also their non-overlapping contacts.

Take a Strategic Approach

They suggest therefore that women can benefit from taking a strategic approach to networking.

• Embrace diversity. The more you associate with people of similar knowledge and experience the less likely you will be to diversify your network and inner circle. It can feel socially secure to be with like-minded people but fail to generate key insights and opportunities. There’s nothing wrong with being in such groups, but try to complement them with others representing more diverse experience and connections.

• Seek quality over quantity. A good network in this context is less about how many people you know but who those people are. So identify and connect with people who are themselves connected to multiple networks.

• Identify female sponsors and advocates. Connect with women in higher positions than yourself and women in organisations you may wish to join, those who can provide you with insider information and advice on how to make the best of yourself. And, in the spirit of ‘pay it forward’, offer the same opportunities to other women.

Uzzi’s study suggests that women face a greater challenge in networking to find professional opportunities. Consequently, they, more than men, need to maintain both wide networks and informative inner circles to help land the best positions. The good news is that by taking a smart approach, women can continue to find meaningful advancement options, while helping their peers and more junior contacts do the same.